Important note: Information on this page was accurate at the time of publication. This page is no longer being updated.

The Results of VOICE: Vaginal and Oral Interventions to Control the Epidemic

I. About VOICE

1. What was the aim of the VOICE study?

VOICE – Vaginal and Oral Interventions to Control the Epidemic – was a major HIV prevention trial designed to evaluate whether antiretroviral (ARV) medicines commonly used to treat people with HIV are safe and effective for preventing sexual transmission of HIV in women. The study focused on two ARV-based approaches: daily use of an ARV tablet – an approach called oral pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP; and daily use of a vaginal microbicide containing an ARV in gel form. Specifically, VOICE sought to determine the safety and effectiveness of three different products: an oral tablet containing tenofovir (known by the brand name Viread®); an oral tablet that contains both tenofovir and emtricitabine (known as Truvada®); and tenofovir gel, a vaginal microbicide formulation of the oral tenofovir tablet. VOICE began in September 2009 and was completed in August 2012.

2. Who conducted and funded the study?

As a flagship study of the Microbicide Trials Network (MTN), VOICE was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), with co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver Institute for Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), all components of the U.S. National Institutes of Health. It was led by Zvavahera Mike Chirenje, M.D., from the University of Zimbabwe-University of California San Francisco in Harare; and Jeanne Marrazzo, M.D., M.P.H., from the University of Washington in Seattle. The study products were provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc., of Foster City, Calif., and by CONRAD, of Arlington, Va. Viread (oral tenofovir) and Truvada are registered trademarks of Gilead Sciences. In 2006, Gilead assigned a royalty-free license for tenofovir gel to CONRAD and the International Partnership for Microbicides of Silver Spring, Md.

3. Where was VOICE conducted, and who participated?

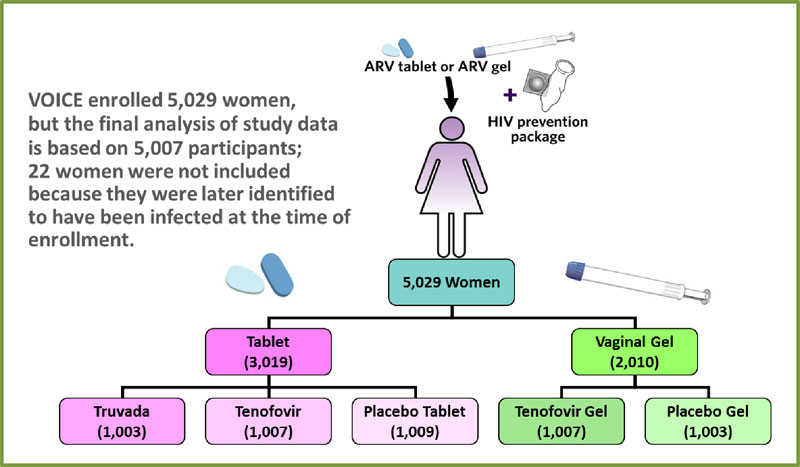

VOICE was conducted at 15 NIAID-funded clinical research sites in South Africa, Uganda and Zimbabwe, encompassing a region where HIV incidence is among the highest anywhere in the world. The study enrolled a total of 5,029 sexually active HIV-negative women: 4,077 in South Africa; 322 in Uganda; and 630 in Zimbabwe. Nearly half of the participants were under the age of 25 and most were not married.

4. Did participants differ by country?

Women in South Africa were generally younger (mean age 24.7); while in Uganda and Zimbabwe the mean age was 28.3 and 28.1, respectively. While only 8 percent of the South African participants were married, in Uganda, 55 percent were married, and 94 percent of the women in Zimbabwe were married. Participants in Uganda were the least educated, with only 3 percent having greater than a secondary school education, compared to 54 percent of the South African participants and 60 percent of the women from Zimbabwe.

5. How was VOICE designed?

Determining the safety and effectiveness of each approach (daily use of tenofovir tablets, Truvada tablets or tenofovir gel) required the kind of trial in which participants were randomly assigned to different study groups, including groups that used a placebo, which has no active drug. Moreover, because the study was “blinded,” neither participants nor researchers knew who was in which group during the study. Like all HIV prevention trials, women in VOICE received HIV risk reduction counseling, condoms and diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted infections – standard measures for preventing HIV – throughout their participation.

VOICE originally had five study groups (also called arms) – two gel groups (tenofovir gel and a placebo gel) and three tablet groups (tenofovir, Truvada and a placebo tablet) – with about 1,000 women in each group who were instructed to use their assigned study product every day. In late 2011, VOICE stopped testing oral tenofovir and tenofovir gel, however, after separate routine reviews of study data by the trial’s independent data safety and monitoring board (DSMB) determined that while each was safe, neither was effective in preventing HIV compared to its matched placebo. VOICE continued to evaluate Truvada until the scheduled end of the study.

II. What VOICE Found

6. When and where were the results of VOICE reported?

Primary results – addressing the study’s main questions about the safety and effectiveness of the products, as well as adherence to product use – were presented at the 20th Conference of Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) 4 March 2013 in Atlanta and were reported in greater detail in the 5 February 2015 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine. Additional results from sub-studies or secondary data analyses have also been reported. Several other manuscripts and abstracts are in development.

7. What are the primary results of VOICE?

None of the three products tested in VOICE (Truvada tablets, tenofovir tablets and tenofovir vaginal gel) was effective among the women enrolled in the trial. Tenofovir gel reduced the risk of HIV by only 14.7 percent compared to a placebo gel, a finding that was not statistically significant. Estimates of effectiveness for both oral tenofovir and Truvada were less than zero (-49 percent for tenofovir and -4.4 percent for Truvada). HIV incidence – the number of women for every 100 who acquired HIV per year – was 5.7 percent, nearly twice what had been expected. HIV incidence was 8.8 percent for unmarried women younger than 25, more than 10 times higher than that in older, married women in VOICE, in whom incidence was less than 1 percent. No safety concerns were identified.

Although adherence to product use was calculated to be about 90 percent based on what the participants themselves had reported to trial staff and on monthly counts of unused gel applicators and leftover pills, tests of stored blood samples indicate that most participants did not use their assigned products daily as recommended. Young, single women were the least likely to use the products and also the most likely to acquire HIV.

8. How was effectiveness determined?

To determine the effectiveness of each approach, researchers compared the number of HIV infections that occurred among women who received an active product with the number of infections that occurred among women in the matched placebo group. While 5,029 women enrolled in VOICE, effectiveness was determined based on 5,007 women; 22 were not included in the final analysis because they were later identified to have been infected at enrollment. Of these 5,007 participants, 312 women acquired HIV during the study.

I n the Truvada group, 61 of 994 women acquired HIV compared to 60 of 1,008 in the oral placebo group. Of the 1,002 women in the oral tenofovir group, 60 acquired HIV, but the efficacy analysis was based on 52 infections in this group and 35 in the oral placebo group to reflect what had occurred up until Oct. 3, 2011, when sites began informing participants that testing of oral tenofovir was to stop. Of the 1,003 women assigned to use tenofovir gel, 61 women acquired HIV, and 70 infections occurred among the 1,000 women in the placebo gel group.

n the Truvada group, 61 of 994 women acquired HIV compared to 60 of 1,008 in the oral placebo group. Of the 1,002 women in the oral tenofovir group, 60 acquired HIV, but the efficacy analysis was based on 52 infections in this group and 35 in the oral placebo group to reflect what had occurred up until Oct. 3, 2011, when sites began informing participants that testing of oral tenofovir was to stop. Of the 1,003 women assigned to use tenofovir gel, 61 women acquired HIV, and 70 infections occurred among the 1,000 women in the placebo gel group.

9. Were there differences in outcomes by country or region?

HIV incidence in VOICE ranged from 0.8 in Zimbabwe to 2.1 in Uganda to 7 percent in South Africa. At some South African sites in the KwaZulu-Natal Province, it was nearly 10 percent. The most profound differences in outcomes were not by country but by demographic group, with young, single women adhering to product use the least and being the most at risk of getting infected compared to older women who were married.

10. How can you really know that a product is effective when you tell participants to use condoms?

As in all HIV prevention trials, researchers conducting VOICE provided participants free condoms and HIV risk-reduction counseling, among other measures, for reducing their risk of HIV. Yet, women cannot always convince their partners to use condoms. So, despite all that was provided to study participants, the reality is that some women will still acquire HIV, and this will be true across all groups. So, at the end of the study, comparing the number of women in the group using the active product who get infected with the number who get infected in the placebo group is still a reliable way to indicate whether or not the product help protect against HIV.

11. What did tests of blood reveal about women’s use or nonuse of the products?

Tests were conducted of women’s blood samples from during the trial to look for the presence of drug – an indication that the product had been used. In a cohort of 647 participants randomly selected from among those assigned to use an active product, drug was detected in 29 percent of blood samples from women in the Truvada group, 30 percent of samples in the oral tenofovir group and 25 percent among those in the tenofovir gel group. Most women were not using their assigned products from the start. Drug was detected in less than 40 percent of the samples of women in the cohort three months into the study, when the first samples were drawn. In many women, drug was not detected in any blood sample taken at any time during the study, suggesting they may have never used the products at all. This was the case for 70 percent of women in the Truvada group, 83 percent in the tenofovir group and 72 percent in the tenofovir gel group.

12. Were any of the products effective among women who did use them?

Additional analysis of the cohort (see above) showed that women in the tenofovir gel group who had drug detected in the sample taken at their first quarterly visit were 66 percent less likely to acquire HIV than those who did not have drug detected, a result that was statistically significant. There was no association between product use and HIV protection with either of the two tablets. While encouraging, conclusions about the gel’s effectiveness can’t be made from this kind of analysis, in part because it involved a very small percentage of the total number of women in VOICE.

13. Why did most women not use the products? What do the VOICE C and VOICE D sub-studies reveal?

Two social and behavioral research sub-studies of VOICE – VOICE C and VOICE D – were conducted to try to address some of the most important questions about VOICE, including why most women hadn’t used the study products despite receiving ongoing counseling on the importance of adhering to the study regimens and living in communities severely impacted by HIV.

The Community and Adherence Sub-study, or VOICE C, was conducted in parallel with VOICE and designed to identify factors within women’s communities, social groups and households that may have influenced their willingness or ability to follow the daily regimens. It was conducted at a single site – Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute (Wits RHI) in Johannesburg, South Africa – and included 102 women enrolled in VOICE, as well as 26 male partners, 17 members of the site’s Community Advisory Board (CAB) and 23 community stakeholders, for a total of 164 participants. Its results suggest women didn’t use the products because they worried about their side-effects and the stigma associated with products meant for those infected with HIV; were ambivalent about being in a trial in which they didn’t know whether they’d been assigned to use an active product or placebo; and felt pressure from partners, family and friends.

VOICE D was conducted after VOICE and involved women in all three trial site countries. Stage 2 of VOICE D was implemented in response to VOICE results and involved 127 former participants who took part in in-depth interviews and/or focus group discussions after learning the results of blood tests indicating their actual patterns of product use during the trial. The researchers hoped that sharing individual test results would elicit candid discussion about the challenges women experienced in using the products. Many of the women at first acted surprised; some insisted the blood tests were wrong, but most opened up about why they hadn’t used the study products in VOICE. The most common themes that emerged were fears about the products and their side effects, which were primarily fueled by other participants, relatives and community members’ negative attitudes about the products.

14. What did VOICE find with regard to tenofovir gel and HSV-2?

While the main questions VOICE was designed to ask concerned prevention of HIV, the team amended the protocol to explore whether any of the products also helped to protect women from acquiring herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) in response to results from another study called CAPRISA 004. CAPRISA 004 found tenofovir gel used before and after sex reduced the risk of HIV by 39 percent and, unexpectedly, also reduced the risk of HSV-2 by 51 percent compared to placebo, the first time that any biomedical prevention method was shown to be effective against HSV-2.

In VOICE overall, there was very little difference in rates of HSV-2 acquisition between the tenofovir gel and placebo gel groups, most likely because of low adherence to product use in the trial. However, further analysis of data involving more than 500 women in the tenofovir gel arms found that HSV-2 risk was reduced by half (47 percent) among women whose tests of blood indicated they used the gel regularly compared to women who seldom or never used the gel (who had no detectable drug in their blood samples), a finding that was statistically significant and was adjusted to account for other potential risk factors, including age, marital status and number of sex partners. Additional data is still needed, however. FACTS 001, a Phase III trial that tested tenofovir gel used before and after sex (the same regimen as in CAPRISA 004), was designed specifically to determine whether the gel was safe and effective in reducing the risk of HIV and HSV-2 in 2,059 women in South Africa.

15. Were the products safe?

Yes; there were no safety associated with any of the products.

16. Did the products cause HIV?

No. The products cannot and did not cause HIV. But unprotected sex can, so VOICE provided participants free condoms, ongoing HIV risk-reduction counseling, among other measures, to help protect them from acquiring HIV.

17. Was resistance a problem among women who acquired HIV?

As with other trials of ARV-based prevention, HIV drug resistance was very rare. Among 301 participants who acquired HIV after randomization, there was one case of emtricitabine resistance detected.

18. Was there an increased risk of HIV associated with women’s use of injectable contraception?

One of the exploratory objectives in VOICE aimed to understand whether there were differences in HIV risk among women using different injectable contraceptives. The analysis focused only on the women enrolled at VOICE’s 11 sites in South Africa, where both DMPA (widely known by its marketed name Depo-Provera®) and NET-EN (or Noristerat®) injectable contraceptives are popular methods of birth control. The results of this analysis, which was the first head-to-head observational study to directly compare differences in HIV risk between users of DMPA and NET-EN, found that women who used DMPA were more likely to acquire HIV than women using NET-EN. As an observational study, the data cannot explain why these results occurred, nor presume that one thing caused another.

19. What was the aim of VOICE B, or the Bone Mineral Density Sub-study? Are there results?

Tenofovir and Truvada are ARVs commonly used in the treatment of HIV. Although they are considered safe and effective for treating people with HIV as part of combination drug therapy, modest decreases in bone mineral density (thinning of bone) have been observed in HIV-infected people during treatment with these drugs. As such, VOICE B, also known as the Bone Mineral Density Sub-study, was an observational study in a subset of participants in VOICE designed to explore the potential effects, if any, that daily use of oral ARVs may have on bone health in HIV-negative women, and in particular, pre-menopausal women in Africa. While African women generally have higher bone mass density than women elsewhere in the world, there may be other factors that could put them at risk for bone loss. VOICE B involved 518 women from Uganda and Zimbabwe who were assigned to one of the oral tablet regimens (oral tenofovir, oral Truvada or oral placebo) in VOICE. Preliminary results found that daily use of tenofovir or Truvada was associated with small decreases in bone mineral density. However, bone mass increased to base-line levels after women stopped using the products.

III. At the Trial Site

20. How did VOICE protect the safety and wellbeing of participants?

VOICE included numerous measures to monitor and protect the safety and wellbeing of participants, beginning at the trial sites with clinical research teams who performed thorough checks on the health, safety and welfare of participants at each monthly study visit. Safety was also monitored by a team at the MTN statistical and data management center that assessed incoming reports on a daily basis; and a VOICE protocol safety review team that provided regular monthly oversight. An independent group of clinical research experts, bioethicists and statisticians called a data safety monitory board, or DSMB, also conducted regular reviews of blinded data while VOICE was in progress. The DSMB conducted four routine reviews of safety data and three reviews for efficacy, and at no time did the DSMB have any major concerns about the safety of the products.

21. What happened to women who acquired HIV during VOICE?

Despite the study’s intensive efforts to reduce participants' risk of HIV, some women became infected during the study due to sexual activity with an HIV-infected partner. Women in the trial who tested positive for HIV were taken off study product immediately and were counseled and referred by study staff to local HIV care and support services. When possible, they were also referred to other local research studies for HIV-infected women. In addition, they were invited to participate in another MTN study called MTN-015. Although MTN-015 does not provide HIV treatment, it provides frequent laboratory tests indicating how the disease is progressing and how women are responding to treatment that can help local treatment service providers better manage the care of these women.

22. Why were women in VOICE required to use contraception?

As with any HIV prevention trial of an unproven biomedical intervention, great attention is paid to the safety and well-being of participants. Because it was not known how the study drugs might affect a woman’s pregnancy or the development of her fetus, only women who were willing to use an effective contraceptive throughout the study were enrolled.

23. What happened to women who became pregnant during VOICE?

Women who did become pregnant stopped using the study products but could remain in the study and continue with all regular follow-up visits. Women were also referred to available sources of medical care and services that they or their babies may have needed. In addition, they were invited to participate in MTN’s Prevention Agent Pregnancy Exposure Registry (MTN-018), also known as EMBRACE (Evaluation of Maternal and Baby Outcome Registry After Chemoprophylactic Exposure), which is a first-of-its-kind observational study of women who become pregnant during an HIV prevention trial and pregnant women who participated in separate MTN safety studies.

24. Did women participating in VOICE provide informed consent?

Yes. Women who volunteered to join the study were told about all the study procedures, any possible risks, benefits and alternatives to participation as well as the study’s time requirements. Study staff also explained that women did not have to join and could leave the study at any time, without consequence. This process, called informed consent, occurred prior to screening for the study, again at enrollment, and continued throughout the duration of the study. Information was provided in simple terms and translated into local languages. Site community educators and CAB members also played important roles in helping participants understand the study, as well as outcomes of DSMB reviews and new information from other studies.

25. What were the medical benefits for women participating in the study?

Study participants received free laboratory tests and physical exams, HIV prevention counseling and free condoms; STI risk-reduction counseling, testing and treatment were provided at no charge to both women and their partners. In addition, VOICE provided effective contraception and monthly pregnancy and HIV testing services.

26. Were participants in VOICE counseled about the importance of adherence?

Participants were counseled at each visit about the importance of adhering to the study regimens, product use and safe sex practices. Moreover, participants were informed of results of other studies that found the same products effective when used consistently, such as CAPRISA 004, which tested tenofovir gel used before and after sex, and the Partners PrEP Study, which evaluated daily use of Truvada and tenofovir tablets.

27. How was adherence measured in VOICE?

To understand how well participants adhered to product use, as well to gain insight into the type of approach women would likely use consistently, VOICE participants were asked questions about sexual activity, product use, male condom use and product sharing, at different time points during the trial. Participants also answered similar questions privately with the help of a computer. At each study visit, pharmacy staff also counted the number of leftover pills and unused applicators. Objective laboratory methods for determining the presence of drug in samples of participants’ blood, vaginal fluid and hair were also used.

IV. Context and Implications

28. Why are the results of VOICE important?

Globally, women account for more than half of the more than 35 million people living with HIV/AIDS. In sub-Saharan Africa, six out of 10 new HIV infections in adults occur in women, with young women aged 15 to 24 especially vulnerable. Women are twice as likely as their male partners to acquire HIV during sex. Although correct and consistent use of male condoms has been shown to prevent HIV infection, often women are not able to choose if they are used. The results of VOICE speak not only to the urgent need for safe and effective methods for women but also to the need for methods that this high-risk population will actually use. Young, unmarried women were least likely to use the study products in VOICE and the most likely to acquire HIV, suggesting that daily use of a product – whether a vaginal gel or an oral tablet – is not the right HIV prevention approach for young African women like those in VOICE. VOICE results are consistent with those of the FEM-PrEP Study, which involved a very similar population of women and also did not find Truvada effective. As in VOICE, most of the participants in FEM-PrEP did not follow the daily regimen. Approaches offering long-acting protection may be more suitable for these women. In fact, two ongoing trials – ASPIRE and The Ring Study – are evaluating a vaginal ring containing the drug dapivirine that women use for a month at a time. A number of other approaches are in early phase testing such as long-acting, injectable antiretroviral agents and new vaginal products.

29. How has VOICE changed the way other trials are conducted?

Certainly, the results of VOICE have caused current trials to reevaluate and/or strengthen their efforts to enhance product adherence, including helping current and prospective trial participants and local communities better understand the importance of correct and consistent product use and the impact that non-adherence can have on the findings of a research study. Many of these trials have already incorporated ways to better understand product adherence while the trial is underway so that the researchers can be made aware of and address challenges as they occur. In ASPIRE, for example, participant blood samples are being tested on a routine basis to determine the presence of active drug, but in a way that preserves the blinded, placebo-controlled nature of the study.

30. What is known about Truvada for HIV prevention?

Oral tenofovir (tenofovir disoproxil fumarate), known by the brand name Viread®, and Truvada, a combination tablet that contains tenofovir and emtricitabine, are both approved for the treatment of HIV when used in combination with other ARVs. In July 2012, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Truvada also for HIV prevention, based primarily on the results of two pivotal studies involving two different populations. The Partners PrEP Study involved 4,758 heterosexual couples in which one partner has HIV, while the iPrEx Study enrolled 2,500 men who have sex with men (MSM). In Partners PrEP (which tested both tenofovir and Truvada), there were 75 percent fewer infections among those who took Truvada compared to placebo (tenofovir was also very effective), while in iPrEx, Truvada was associated with a 42 percent reduction in HIV risk. A smaller trial of 1,200 heterosexual men and women in Botswana found Truvada reduced the risk of HIV by 62 percent. These same studies also demonstrated that Truvada was more effective when the daily regimen was followed consistently. Indeed, as with VOICE, Truvada was not effective in the FEM-PrEP Study, and many of its participants – 2,119 women from Kenya, South Africa and Tanzania – did not follow the daily pill-taking regimen as instructed.

31. With such mixed results, what can be concluded about Truvada for preventing HIV in women?

Partners PrEP provides strong evidence that Truvada used daily is an effective approach for older women in a stable relationship with a partner they know has HIV, while FEM-PrEP and VOICE suggest such an approach is unlikely to work for younger, single women in Africa. Although results of the TDF2 in Botswana showed that Truvada was effective in both men and women, few conclusions can be drawn from the results concerning the effectiveness of Truvada specifically in women due to the small numbers of women who became infected during follow-up.

32. What is known about tenofovir gel?

Tenofovir gel is a vaginal microbicide that contains the same active ingredient as the oral tablet formulation of tenofovir. The CAPRISA 004 study found that tenofovir gel used before and after sex reduced the risk of HIV by 39 percent, a finding that was considered a major milestone for the field. The study, which involved 889 women at two sites in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa, unexpectedly found tenofovir gel also reduced the risk of HSV-2 by 51 percent, the first time a biomedical prevention method was shown to be effective against HSV-2. FACTS 001, a Phase III trial of the same regimen (before and after sex) that enrolled 2,059 women at nine South African sites, hopes to replicate the CAPRISA 004 findings, with results expected in February 2015.

33. How could tenofovir gel not be effective in VOICE when the CAPRISA 004 study found that it was?

It is not unusual for results of trials to differ. That’s exactly why more than one trial is needed before making definitive conclusions about a particular intervention for its use in different populations. Yet, while the results of CAPRISA 004 and VOICE appear to differ, they are actually similar. CAPRISA 004 found tenofovir gel reduced the risk of HIV by 39 percent among women who used it before and after vaginal sex compared to women who used a placebo gel. But it is important to consider another statistical measure called a confidence interval, which in CAPRISA 004, suggests the true level of effectiveness of tenofovir gel could be anywhere between 6 and 60 percent. Although VOICE tested a daily regimen of tenofovir gel, and its results were not statistically significant, tenofovir gel was estimated to reduce the risk of HIV by 14.7 percent compared to the placebo gel—a result within the range of that of the CAPRISA 004 study – with a confidence interval indicating the level of effectiveness could be between -21 percent and 40 percent.

34. How will results of VOICE affect efforts to license tenofovir gel?

As a co-licensee for tenofovir gel, CONRAD has been leading all discussions with drug regulatory authorities, including with the FDA and the South African Medicines Control Council in support of the gel’s possible approval, with CAPRISA 004 and FACTS 001 the two licensure trials. VOICE results and data from a large portfolio of studies conducted by both the MTN and CONRAD will also be considered.

35. What are the implications of VOICE results on tenofovir gel’s development as a rectal microbicide?

MTN researchers are conducting studies of a different formulation of tenofovir gel with less glycerin for use by both men and women as a rectal microbicide to protect against HIV acquired through anal sex. The reduced glycerin formulation gel was found safe and acceptable in a Phase I study called MTN-007 and is now being evaluated in a Phase II trial called MTN-017. In MTN-017, researchers are evaluating the rectal safety, drug absorption and acceptability of the reduced glycerin formulation of tenofovir gel, as well as oral Truvada, at sites in Peru, South Africa, Thailand and the U.S., including Puerto Rico. The study, which has enrolled 195 MSM and transgender women, is the first Phase II trial of a rectal microbicide. Follow-up is expected to be completed mid-2015 and results available late 2015 or early 2016.

36. What HIV prevention trials are currently being conducted in women?

Two Phase III studies — The Ring Study and ASPIRE — are being conducted across more than 20 sites in Africa to determine whether a monthly vaginal ring that releases an ARV drug called dapivirine prevents HIV infection in women and is safe for long-term use. Because women only need to replace the ring once a month, it could provide a discreet and easy-to-use new method of protection. ASPIRE – A Study to Prevent Infection with a Ring for Extended Use – is being conducted by the MTN. The Ring Study is being conducted by the International Partnership for Microbicides (IPM), which developed the dapivirine ring. Together, these “sister” studies involve more than 4,500 women volunteers across southern and eastern Africa, and are expected to provide the evidence needed for possible regulatory approval and licensure of the ring. Results of ASPIRE are expected late 2015 or early 2016; efficacy data from The Ring Study is likely to be available within the same timeframe.

# # #

More information about the VOICE Study is available at http://www.mtnstopshiv.org/news/studies/mtn003.

Click here for PDF version of this document.

4-February-2015